Conservation programs are a significant part of federal farm policy, even if they haven’t garnered the same headlines as commodity programs traditionally do, or as major policy proposals have in recent weeks.

Headlines

For the agricultural community, commodity programs are traditionally the major driver of policy discussion and focus during the regular development of farm bills every five years or so. That is not to say that agricultural groups don’t pay attention to conservation programs or that they don’t work with coalition partners to support major conservation initiatives, but they tend not to be the primary focus for many. Yet, conservation program spending in the farm bill rivals that reserved for commodity programs. When the 2018 Farm Bill was passed, conservation program spending was projected by the Congressional Budget Office at $59.7 billion over the 10 federal fiscal years from 2019-2028, nearly as much as commodity programs at $61.4 billion. These projections don’t preclude the likelihood that program costs will vary from budget according to economic conditions or annual appropriations, but it does confirm that conservation is a significant part of the farm portfolio in the farm bill.

Of course, recent programs and headlines have also overwhelmed much of the discussion about underlying farm bill programs like conservation. Over the past three years, 2018-2020, ad hoc payments for trade losses, disaster assistance and COVID relief have exceeded total commodity and conservation program spending combined ($57.5 billion vs. $24.8 billion), leaving the underlying farm bill programs as almost an afterthought with additional COVID relief continuing in 2021.

Thus far in 2021, new initiatives and policy proposals on climate, carbon, and national conservation goals have garnered the headlines. Climate commitments from numerous corporate entities, the growth of several carbon market integrators, and even the resurrection of a futures market in Chicago for carbon credits signal potential new opportunities for producers and landowners. The Growing Climate Solutions Act of 2021, recently passed by the Senate, would position USDA to help farmers, ranchers and private forest owners generate and market environmental credits. Other policy proposals envision a larger role for USDA in banking carbon credits or incentivizing carbon sequestration practices, such as the cover crop incentive payment for producers, announced earlier this year as part of the larger Pandemic Assistance Program. And, of course, the Biden Administration’s 30x30 conservation plan fits into the discussion as well, although the details, while much discussed, remain relatively lacking about the role of the federal government in controlling and managing resources versus incentivizing stewardship of private land and resources.

Conservation Programs

While new market opportunities and policy proposals may be on the doorstep, existing federal conservation programs already provide a substantial federal investment in conservation on private land. As covered in a recent webinar, there are numerous conservation programs that provide the voluntary carrot to motivate and reward environmental efforts through the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) for land retirement, the working lands programs such as the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP) to preserve farmland and wetlands, and the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) to target local priorities and leverage federal and local funding.

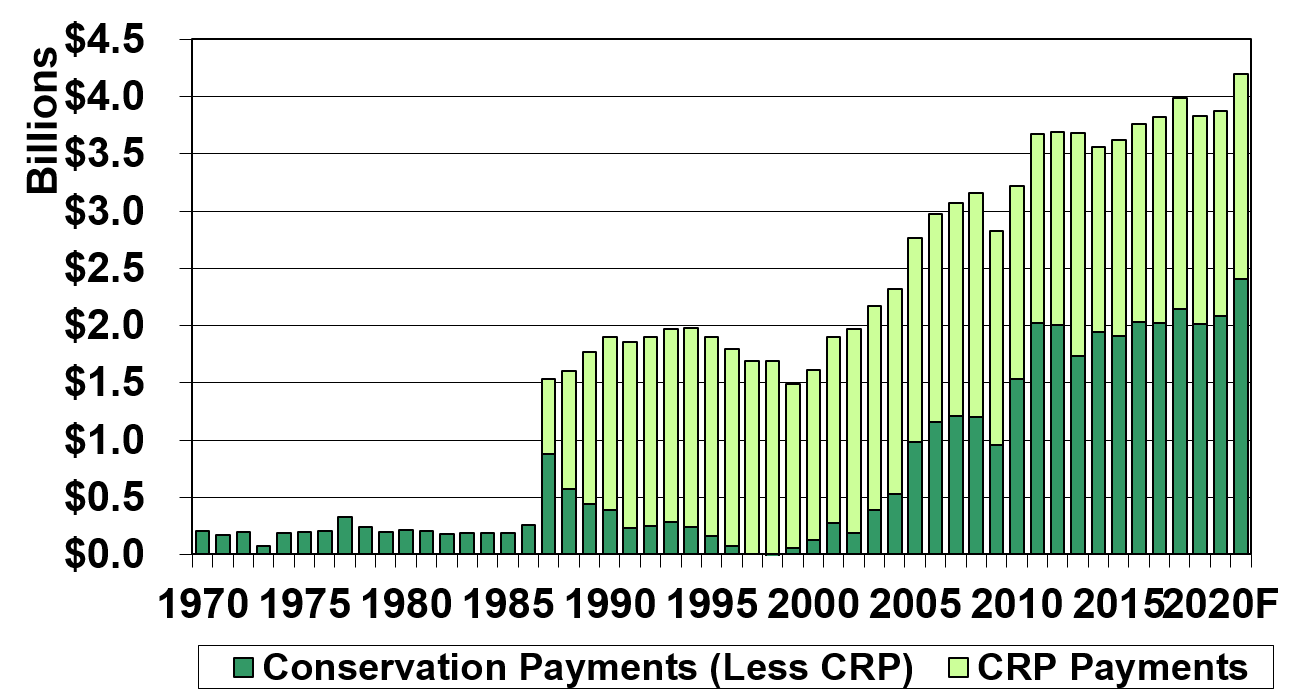

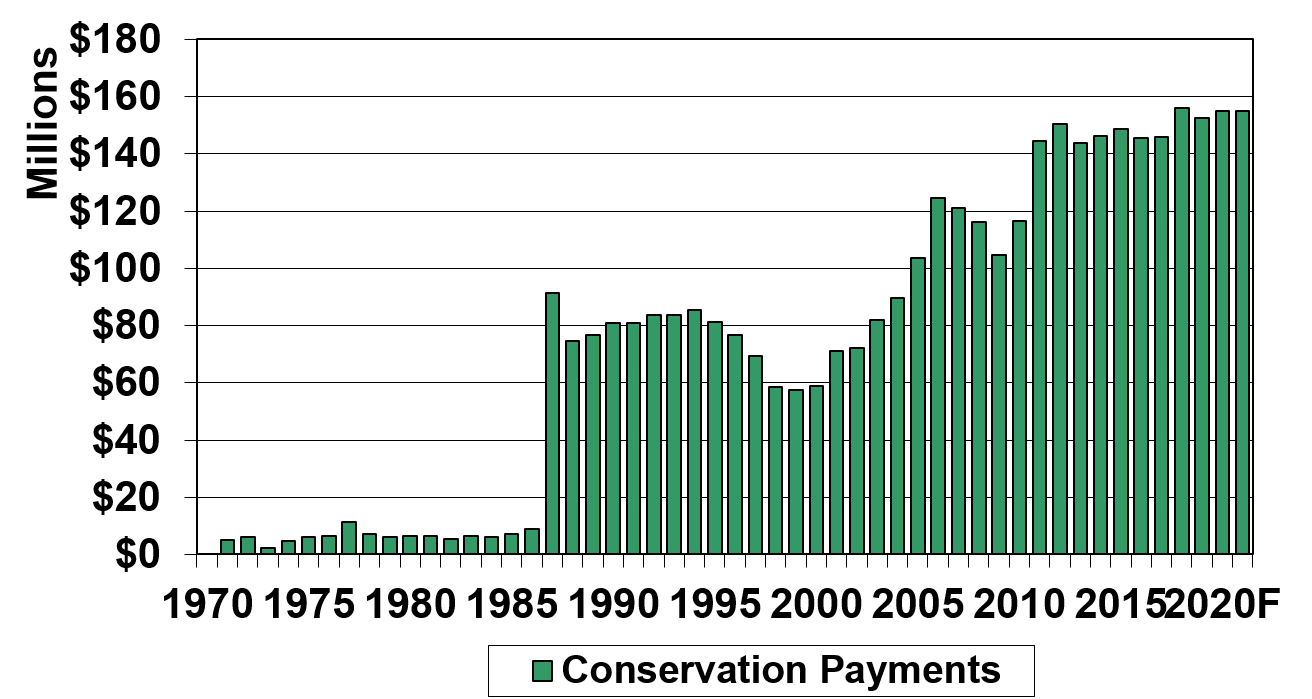

Over the past 35 years, spending on these voluntary conservation programs has grown dramatically. Nationally, conservation payments to producers have grown from less than $300 million per year in the 1970s and early 1980s, to nearly $4 billion per year throughout the 2010s. Nebraska has been a significant participant in these voluntary programs, with payments growing from less than $10 million per year in the early 1980s to more than $150 million per year at present.

Figure 1. Conservation Payments — United States

Figure 2. Conservation Payments - Nebraska

A significant part of the conservation program growth was the CRP, in which Nebraska currently has about 1.2 million acres enrolled out of nearly 21 million acres nationwide, earning more than $73 million annually in CRP rental payments, not counting any additional income received from managed haying or grazing or from providing environmental services such as hunting access. Nebraska is also a leading participant in the EQIP and CSP working lands programs that provide producers cost-share assistance or incentive payments for adoption and maintenance of targeted conservation practices. For federal fiscal year 2020, Nebraska was a top-twenty state for total EQIP dollars and a top-ten state for both CSP dollars and acres, with nearly a million acres currently enrolled in active EQIP and CSP contracts.

In sum, Nebraska producers and landowners have been active participants in federal conservation programs and have been rewarded in part for protecting the nation’s privately held natural resources and adopting good conservation practices. The growth of new environmental markets, whether specifically for carbon credits or for broader environmental benefits and services, could bring additional financial rewards to producers and landowners across the state. There is a great deal of uncertainty about both the opportunities and the potential policy directions ahead. However, the existing portfolio and support are already significant now and have the potential to grow substantially in the future.