A webinar covering the market implications of the Lexington plant closure was held on Dec. 4, 2025. Watch the recording here.

At a Glance

- The Lexington plant closure is permanent, unlike past disruptions such as the 2019 Holcomb fire.

- National cattle supplies remain at a 70-year low, limiting packers’ ability to operate plants at full capacity.

- Short-term fed and feeder cattle prices fell sharply, with larger impacts expected in central Nebraska.

- Economic research suggests capacity utilization—not market power—is the primary driver of price effects.

- New processing capacity is coming online, but geography and timelines mean it may not fully offset the loss in the near term.

The Situation

On Nov. 21, Tyson Foods announced it would permanently close its beef processing facility in Lexington, Nebraska, effective Jan. 20. The company also announced it would convert its Amarillo, Texas, facility to a single full-capacity shift. The Lexington plant employs roughly 3,200 people and can slaughter almost 5,000 cattle per day, approximately 4.8% of total daily U.S. beef slaughter. This marks the first time one of the "Big Four" meatpacking companies has permanently closed a major plant during the current cattle supply crunch.

Markets have reacted quickly. On Nov. 24, live cattle futures fell the $7.25 daily limit, and feeder cattle futures dropped the $9.25 limit across the board. Cash fed cattle trade the week prior came in at $222-224 per hundredweight in the South (down $4-5) and $218 in the North (down $7). The CME Feeder Cattle Index stood at $339.72 on November 20. Nebraska feeder cattle prices were $10-20 lower for 700-800 lb. steers and $20-40 lower for 500-600 lbs. steers last week.

The purpose of this article is to explain what the Lexington plant’s closure could potentially mean for cattle producers in Nebraska and beyond, how it compares to previous plant disruptions in the last 5-7 years, what economic research tells us about potential price impacts of such a closure.

Background on Tyson and the Beef Packing Industry

Tyson Foods is one of the four largest beef packers in the United States. Together, the “Big Four” — Tyson, JBS, Cargill, and National Beef — control approximately 83-85% of U.S. beef processing capacity. This high level of concentration has long been a point of concern for cattle producers regarding market power and price discovery.

Table 1. Estimated Beef Packer Summary Statistics (2022): Fed Cattle Processing

| Firm | Number of Plants | Avg. Capacity (head/day) | Total Capacity |

| JBS | 8 | 3,144 | 25,150 |

| Tyson | 6 | 4,600 | 27,600 |

| Cargill | 6 | 3,700 | 22,200 |

| National Beef | 3 | 4,400 | 13,200 |

| Other | 20 | 921 | 18,415 |

| Total | 43 | 2,478 | 106,565 |

Source: Moschini and Smith (2025), based on Cattle Buyers Weekly and USDA FSIS data. Statistics shown represent the fed cattle processing capacity of the 30 largest U.S. beef packing firms.

Tyson reported that its cattle costs for fiscal year 2025 (which ended in September) rose by nearly $2 billion compared to the prior year. The company posted an adjusted loss of $426 million from its beef business for the year. In their Nov. 10 fiscal report, Tyson projected beef segment losses between $400-600 million for fiscal year 2026, citing a projected 2% decline in domestic beef production.

Beyond the Lexington closure, Tyson has been strategically reallocating assets with some investments going towards case-ready beef operations. The company invested $42 million to transform a closed facility in Columbia, South Carolina, into a case-ready operation and unveiled a $300 million case-ready facility in Eagle Mountain, Utah, that will increase case-ready capacity by nearly 24%. Case-ready products are pre-packaged with consistent sizes, cuts, and weights are designed for online shopping and help retailers reduce in-store labor costs.

Why Is This Happening? The Cattle Supply Situation

The fundamental driver behind the Lexington plant closure is the U.S. cattle supply situation. The national cattle herd is at its lowest level since 1950, a 70-year low. This shortage stems from:

- Multi-year drought in Texas and Southern Plains states that burned up pasture and increased feeding costs

- Improved beef efficiency leading to more beef per carcass due to in part genetic improvements

- Slower-than-expected herd rebuilding due to aging producers, higher interest rates, and producer desires to pay down debt leading to less heifer retention

- Recent disruptions including the closure of the Southern border to Mexican feeder cattle due to New World screwworm concerns

When cattle supplies decline, packing plants may be impacted in two ways. First, they may need to operate below full capacity. “Capacity utilization” is the ratio between observed harvest and potential capacity which typically runs between 83-95% in normal times. In 2025, national slaughter capacity utilization has generally been below 85%, dipping as low as 80%. Second, declining cattle supplies also impact packing plants through increasing cattle prices. Cattle prices increase as packers compete more aggressively for the available supplies. This increases the packing plants’ variable costs, reducing packers’ margins on each head of cattle they process.

These two factors, decreased capacity utilization and increased variable costs, combine to reduce packing plants’ profitability. When this decrease in profitability is large enough and expected to continue, firms may decide to permanently close a plant to reduce their fixed costs (which include plant infrastructure, machinery, and technology) and utilize their remaining capacity more efficiently. The packing industry as a whole has been reducing capacity since 2000 as cattle supplies have trended downward. Recently, some fed plants have been much below normal utilization due to fewer cattle to harvest, with the Lexington plant running below its 5,000 head-per-day capacity.

Lessons from the Temporary Tyson Plant Closure in Holcomb, Kansas

The Tyson plant fire in Holcomb, Kansas, on August 9, 2019, provides an instructive comparison for understanding market reactions. That plant processed approximately 6,000 head per day (about 6% of daily slaughter).

Key lessons from Holcomb included:

- Live cattle prices fell given the sudden oversupply of harvest-ready cattle relative to processing capacity

- Wholesale beef prices increased as retailers rushed to make advance purchases ahead of Labor Day

- Combined, these widened beef processing margins, something intensely watched since 2019

- All major feeding regions experienced about a 10% price decline in the fed cattle price within the first month

- Prices recovered to pre-fire levels approximately two months after the fire

Table 2. Percent Change in Fed Cattle Prices Following the Holcomb Fire (Week of Aug. 11, 2019 = 0)

| Period After Fire | Kansas | Nebraska | Iowa/Minn. | 5-Area Avg |

| Week 1 (Aug 18) | -4.12% | -5.59% | -4.87% | -4.96% |

| Week 4 (Sep 8) | -8.82% | -11.17% | -8.85% | -9.62% |

| Week 5 (Sep 15) | -9.13% | -11.40% | -11.24% | -10.90% |

| Week 8 (Oct 6) | -2.27% | -3.90% | -5.77% | -4.33% |

| Week 12 (Nov 3) | +2.38% | +1.28% | -0.83% | +0.66% |

| Week 16 (Dec 1) | +8.10% | +5.42% | +3.02% | +4.85% |

Source: Dennis (2020)

The two key market questions that kept fed cattle prices low were: (1) when would the plant reopen, if at all? and (2) could remaining plants redistribute the available market-ready cattle? In the Holcomb case, Tyson announced rebuilding plans by late October 2019, and the plant was fully operational by December 2019.

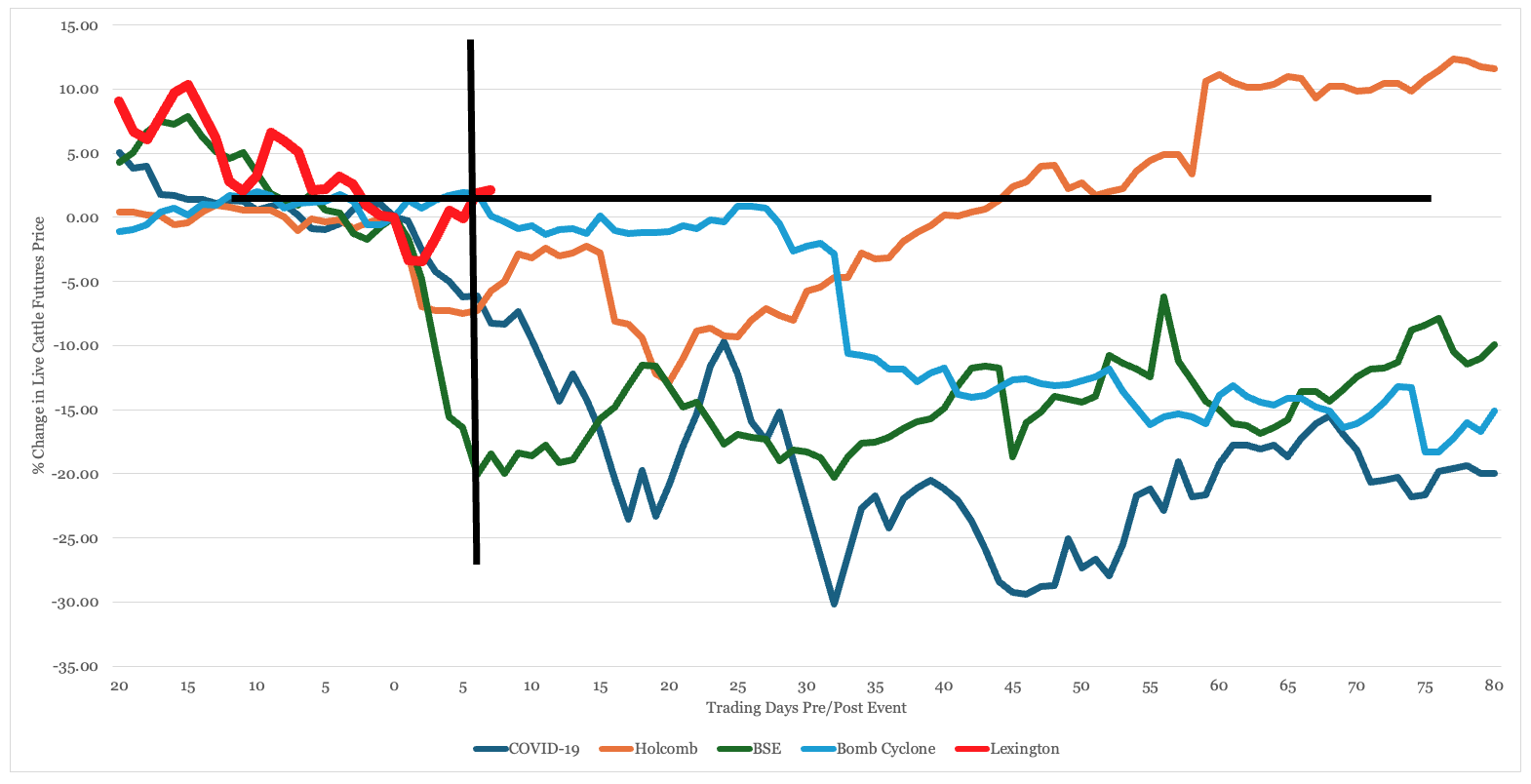

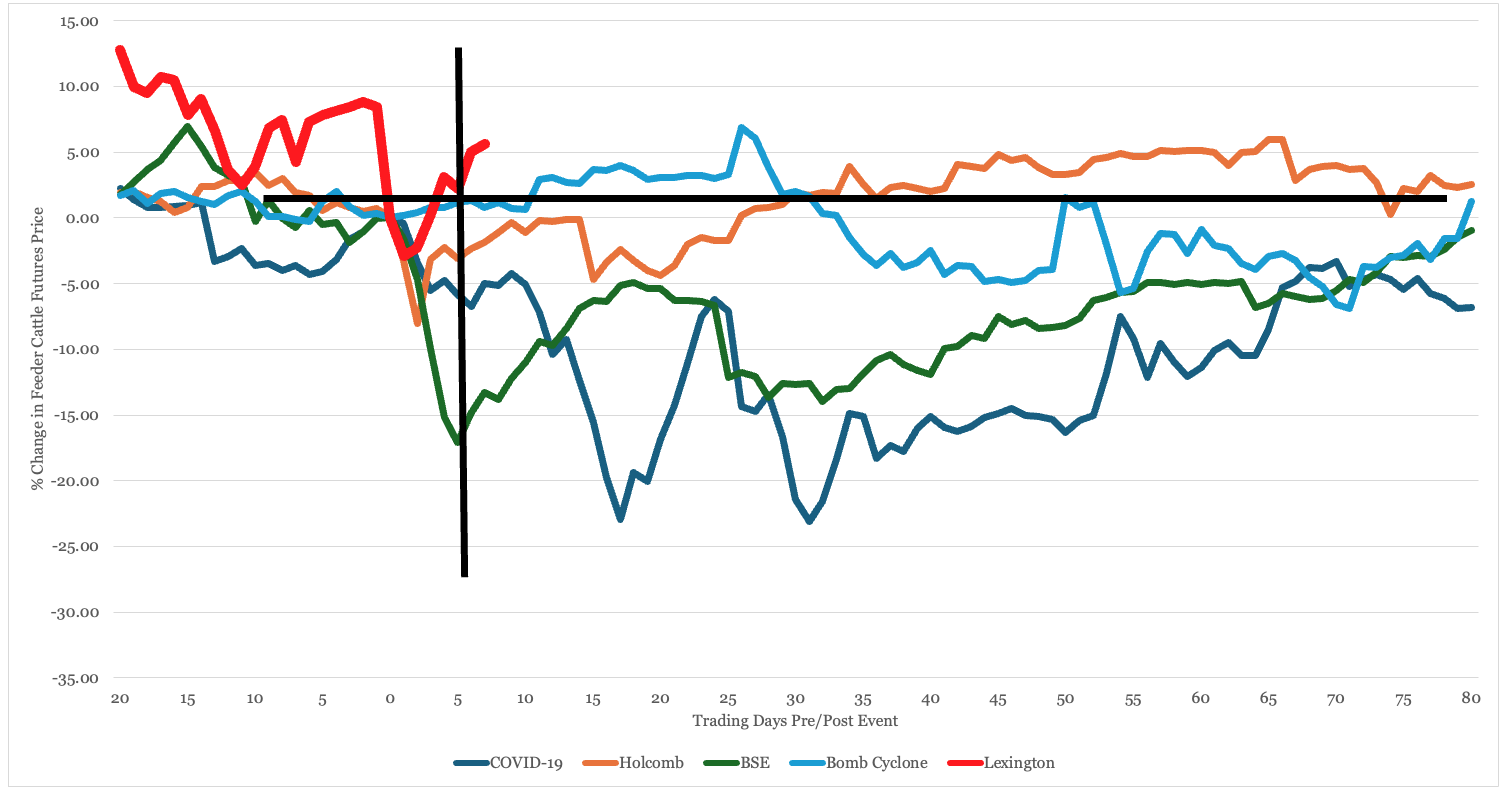

Impact of Plant Closures on Fed Cattle Prices: What Economic Research Tells Us

The critical distinction between fire-related disruptions and the Lexington closure is permanence. While the Holcomb plant reopened within about four months of the fire and plant closure, there are currently no plans or intentions to reopen the Lexington plant for beef packing. This permanence means that the market will reach a new equilibrium with the absence of the Lexington plant. Figures 1 and 2 shows the percentage change in the fed and feeder cattle prices per and post the Lexington plant closure and other plant closure announcements. Since the announcement that markets have largely recovered and the price effects were much smaller than those experienced during the Holcomb plant fire and the COVID-19 plant closures. Prices have been able to recover as the underlying market fundamentals are largely unchanged such that there are fewer cattle to be placed on feed and harvested due to lower feeder cattle imports from Mexico and a smaller herd size due to droughts over several years and record cull cow prices.

Figure 1. Price Impact of Different Plant Closures on the Live Cattle Futures Price.

Source: CME LC Nearby Futures, Authors Calculations

Figure 2. Price Impact of Different Plant Closures on the Feeder Cattle Futures Price.

Source: CME FC Nearby Futures, Authors Calculations

Note: The large drop in the FC contract is pre-announcement as the November FC25 contract closed on Nov 20 and the nearby contract rolled to the January FC26 contract.

The long run implications of a plant closure could be much different. A study by Moschini and Smith (2025) published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics used a computational model of the beef packing industry to examine, among other things, how market equilibrium in the industry may be impacted by a plant exit. This study found that the main driver of price changes after a plant exit is capacity utilization. If a plant exits the market when capacity is already tight, the remaining plants are pressed even further toward their capacity constraints. In this situation, they place a lower value on a marginal head of cattle, and cattle prices will decrease. On the other hand, if a plant exits the market when there is considerable excess capacity, it may have little impact on cattle prices as the remaining plants will still be operating below their capacity constraints.

Because it was caused by an accidental fire, the Holcomb plant’s closure was unplanned for and unexpected. It occurred at a time when cattle supplies and plants’ capacity utilization was significantly higher than today; in January – July 2019 (the months preceding the Holcomb fire), about 11% more cattle were slaughtered nationally than in January – July 2025 (USDA ERS, 2025). Because capacity utilization is lower today than it was in 2019, the industry has more ability to redistribute market-ready cattle, and we’d expect price impacts to generally be smaller than they were after the Holcomb plant closure in 2019. Of course, it is important to note that the price impacts of the Lexington closure will be permanent, while the impacts of the Holcomb closure lasted only a few months.

Another important insight from the Moschini and Smith (2025) is that location matters. Price impacts in the Nebraska and Kansas counties surrounding Lexington will be larger than the national average, as cattle in this region will need to travel farther to alternative plants, increasing transportation costs and shrink for producers.

Historical Precedent: The Cargill Plainview Closure (2013)

The current situation has parallels to Cargill's closure of its Plainview, Texas, plant in February 2013. That plant employed approximately 2,000 workers and processed about 4,650 head per day. Cargill cited:

...tight cattle supply brought about by years of drought in Texas and Southern Plains states” and noted that “the U.S. cattle herd is at its lowest level since 1952.

Cargill's stated rationale is similar to today's situation:

Given the over-capacity that exists with four major beef plants in the Texas Panhandle and a dwindling supply of cattle in the region, idling Plainview will allow Cargill to operate its other beef plants in Texas, Colorado and Kansas more consistently on a five-day-per-week basis.

Cargill initially preserved the infrastructure for potential reopening. However, by September 2015, the company placed the property up for sale, noting that “beef processing overcapacity persists today, and plant closures continue even as conditions have improved in some regions.”

Could the Lexington plant be converted? One possibility worth watching is whether the Lexington facility could be converted to an alternative use. In 2015, Cargill converted its Columbus, Nebraska, ground beef processing facility into a cooked meats facility with an $111 million investment. This type of conversion shifting from live cattle slaughter to value-added processing could preserve some jobs and infrastructure. Whether Tyson would convert or sell the plant is unknown. When Tyson closed a plant in Norfolk, Nebraska, in 2006 the removed all the infrastructure inside the plant so it could not be used and currently remains empty.

New Processing Capacity Brought on Since 2020

New packing capacity has been brought on since concerns about packer concentration in 2020. This was partially spurred on by federal dollars under the Biden, and now Trump administration, to increasing capacity for small and medium processing plants (see https://www.ams.usda.gov/services/grants/localmcap/awards for the list of plants that received funding). Some of these have been complete and others have stalled, delayed, or ceased operating. The total capacity that now is being operated is 4,900 head which is nearly the same amount of capacity reduced by Tyson. However, geography matters and where these plants are being built changes that landscape of cattle feeding. In addition, several other large plants are scheduled to be completed over the next several years.

Table 3. Select Beef Processing Plants Built and Announced

Location (Company) | Status | Current Status | New Capacity (hd/day) |

| Idaho Falls, ID (Intermountain) | Built | Operating | 500 |

| Jerome, ID (Agri-Beef) | Built | Operating | 500 |

| North Platte, NE (Sustainable Beef) | Built | Operating | 1,500 |

| Wright City, MO (America’s Heartland Packing) | Built | Operating | 2,400 |

| Pleasant Hope, MO (Missouri Prime) | Built | Closed | 750 |

| Amarillo, TX (Producer Owned Beef) | Announced | Under Construction | 3,000 |

| Mills County, IA (Cattlemen's Heritage) | Announced | Permitting | 2,000 |

| Rapid City, SD (Unnamed) | Announced | Funding | 8,000 |

Source: Author compilation

Its important to note that some plants are operating and many announced projects have stalled due to financing, permitting, or market conditions. Even the plants that proceed are generally 500-2,500 head/day far smaller than the 5,000 head/day being lost at Lexington. The combined new capacity from plants that are actually built may not fully offset the Lexington closure in the near term.

What to Watch Going Forward

Here are a few things that the industry will be watching for over the next several months.

1. Will the plant change ownership or be converted?

A sale could happen to another packer or investor group, it could be converted to ground beef or case-ready processing (similar to Cargill's Columbus conversion), or it could be permanently closed and all the assets stripped like the Norfolk plant. Governor Pillen noted that Tyson has promised to “continue to work on future value-added opportunities” in the state. Whether this means the Lexington facility specifically remains to be seen.

2. Redistribution of cattle and regional price differentials

Tyson says it will increase production at other facilities including Dakota City, Nebraska; Holcomb, Kansas; Hillsdale, Illinois; and Pasco, Washington. Watch for changes in regional cash price differentials (Table 2 from Holcomb showed Nebraska actually experienced larger price drops than Kansas), increased Saturday/weekend harvest at remaining plants, and whether plants can absorb redistributed cattle without hitting capacity constraints.

3. Formula contract implications

Approximately 70% of fed cattle are now procured through Alternative Marketing Arrangements (AMAs) with base prices tied to negotiated cash market prices. If negotiated trade in the region declines further, this could affect price discovery and the basis used for formula contracts.

4. Timeline and transparency

Unlike the Holcomb fire where Tyson eventually announced rebuilding plans, there is no uncertainty here the plant is closing permanently. The market will need to adjust to this as a structural change rather than a temporary disruption.

Impact on Cattle Producers

The Lexington closure represents a structural shift in the beef packing industry, not a temporary disruption like the Holcomb or Grand Island fires. These are what we believe to be that the closure will have on the beef industry:

- Short-term price pressure is significant. Markets moved limit down, and regional cash markets in Nebraska are likely to feel the most immediate pressure. Historical data from Holcomb suggests price declines of 9-11% in the first month are possible.

- The capacity constraint matters more than market power. Research suggests the bigger issue isn't packers exercising additional market power, but rather the system being stretched to handle cattle supplies with less processing capacity.

- Transportation costs will increase for some producers. Those who previously marketed cattle to Lexington will face longer hauls and associated shrink losses.

- Watch for redistribution effects. How efficiently cattle can be rerouted to other facilities and whether those plants can absorb additional volume will significantly impact how quickly markets stabilize.

- This is about cattle supply, not demand. Consumer demand for beef remains strong. The underlying issue is that the historically small cattle herd means packers cannot run plants at economically viable levels.

- New capacity is coming, but slowly. Plants like Sustainable Beef (North Platte), Cattlemen's Heritage (Iowa), and Producer Owned Beef (Amarillo) are progressing, but timelines extend to 2027 and beyond. Many announced projects have stalled.

The cattle industry has weathered plant disruptions before and will weather this one. But unlike temporary closures, this permanent reduction in capacity may keep markets in a tighter configuration for years at least until new capacity comes online or the cattle herd rebuilds to levels that justify additional large-scale investment.

References

Dennis, E. 2020. "A Historical Perspective on the Holcomb Fire: Differences and Similarities to the COVID-19 Situation and Other Significant Market Events." The Nebraska Cattleman, September 2020. Center for Agricultural Profitability, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Moschini, G., and T.J. Smith. 2025. "Spatial Price Competition and Buyer Power in the U.S. Beef Packing Industry." American Journal of Agricultural Economics. DOI: 10.1111/ajae.70003

Cargill. 2013. “Cargill to idle Plainview, Texas, beef processing plant; dwindling cattle supply cited.” Press Release, January 17, 2013.

USDA Economic Research Service (ERS). 2025. “Livestock and Meat Domestic Data.” https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/livestock-and-meat-domestic-data.

Various news sources including DTN, Reuters, Nebraska Examiner, AgWeb, and RFD-TV, November 2025.